Dungeons & Data

14 May 2020I recently came across a Dungeons and Dragons (D&D) API, designed to support people playing D&D by giving them a quick way to check spell details etc. Not being a D&D player myself, but being interested in both fantasy monsters and data mining, I thought it would be an interesting data source to play around with.

To that end, I extracted as much information about monsters as the API would give me, and started sifting through the data to see if anything interesting jumped out.

Background

Dungeons & Dragons is a tabletop roleplaying game published by Wizards of the Coast. Arguably/probably, it’s the most well-known and influential one ever, casting a long shadow over much of the fantasy genre for the past several decades. Of course, older fantasy such as The Lord of the Rings and Beyond the Fields we Know cast an even longer shadow over D&D itself, but it’s still very important within its scope.

It’s a collaborative roleplaying game, with some players taking on the roles of adventurers - with all sorts of different classes/abilities - and one player taking the role of “dungeon master” (DM), creating the world and animating the monsters.

D&D is famous for, amongst other things, the number and variety of its various monsters. Monsters like the beholder and the owlbear originate from D&D, but have taken on a wider cultural significance. Other D&D monsters were adapted from earlier legendary/folklore sources, but their portrayal within the game has had a definite effect on the way they are widely thought of.

As the game’s name suggests, much of D&D revolves around noble heroes delving deep into dungeons and fighting monstrous creatures. This post describes my delving into monster data in a way that is both similar to, and much less brave, than those adventurers’ expeditions.

Disclaimer

I don’t know much about the specifics of D&D; I have a general cultural knowledge of how it works, etc., but I might say something dumb at any point because I don’t know the rules; please view me as a well-intentioned but naive tourist, and forgive any irritating ignorance.

This post is data-mining D&D from an outside perspective, and some of the things I find interesting might be less so to you if you have prior knowledge. I’m not claiming any definitive analysis, or special authority here, but it’s fair to say that charging in without requisite prior knowledge is a time-honoured dungeon-crawling tradition.

Aims

My analysis was driven primarily by curiosity, rather than any set aim, but there were a couple of questions I was interested in answering:

Are there neglected monster niches?

People create “homebrew” D&D content all of the time, developing new quests and classes and monsters to put in their games. If there are particular kinds or styles of monster that are relatively uncommon, it could be useful to identify them, so that people creating new content can target the most untrodden ground.

Are the raw stats (such as strength and charisma) strongly linked to challenge rating (a monster’s canonical difficulty to overcome)?

Challenge rating (CR) seems - from an outside perspective - to be a bit of an arbitrary figure. Surely so much of the game’s difficulty will depend on player choice, how intelligently the DM plays the undead wizard, etc. I’d like to look at how closely linked the CR of a monster is to its other numeric stats. My initial assumption was that there would be a noticeable trend, but that there would be a lot of noise caused by abilities and such that affected the monster’s difficulty alongside its raw scores.

Motivation

I was motivated to carry out this analysis by four factors, listed in ascending order of importance:

- I’m currently doing the Udacity Data Scientist Nanodegree, and projects are required.

- There’s a very active modding/homebrew community for D&D, and this sort of analysis might conceivably be useful to someone looking to create new monsters, etc.

- It was an opportunity to practice various data-related techniques.

- I found the API and thought it would be fun to play with.

Code

All the code written during this project can be found on Github. I wrote it using Python 3, inside a Jupyter notebook. The linked repository contains a full list of libraries used and commented code explaining what I did to generate the various visualisations explained below.

Data Source

The data for this project was pulled from the Dungeons and Dragons 5th edition API. It’s a really great API to work with - the documentation is very clear, and there are no fiddly authorisation problems.

I made a total of 323 calls to the API - one to get a full list of available monsters, and 322 to pull full details for each of those listed monsters. I stored the whole thing in a Pandas dataframe, and then was good to go. Creating the full dataframe took around a minute.

I’d like to stress that this analysis is only really scratching the surface of what can be done with this data; this is very much the kill n common mobs of data-mining D&D. It could absolutely be taken further and used to do even more exciting things, probably by someone who is both a better data scientist than me and actually a player of the game.

Data cleaning & processing

One of my absolute favourite things about APIs is that - if they’re well-designed and reasonably maintained, almost no data cleaning is required. I dropped a few columns that were mostly empty (very few monsters have legendary actions, for example), but otherwise the data was automatically in a fit state. It was lovely.

In terms of processing the data, I dropped several more columns that were very granular, such as the actions column containing specific details of the various actions each monster was capable of. I wanted to keep the analysis relatively high-level, so I kept only those columns that could be reduced to a single figure/detail for each separate monster.

In order to extract key details - such as which monsters could swim - I had to do a small amount of data manipulation to pull data out dicts into a usable format, but mostly this was a very easy dataset to work with.

Data exploration

In total, the API provided me with data on 322 different monsters. For each one, I had information about its name, size, type (zombies are the “undead” type, for example), moral leanings (more on that later) and various numeric stats, ranging from how strong it was to how difficult it would be to defeat.

Type and Size

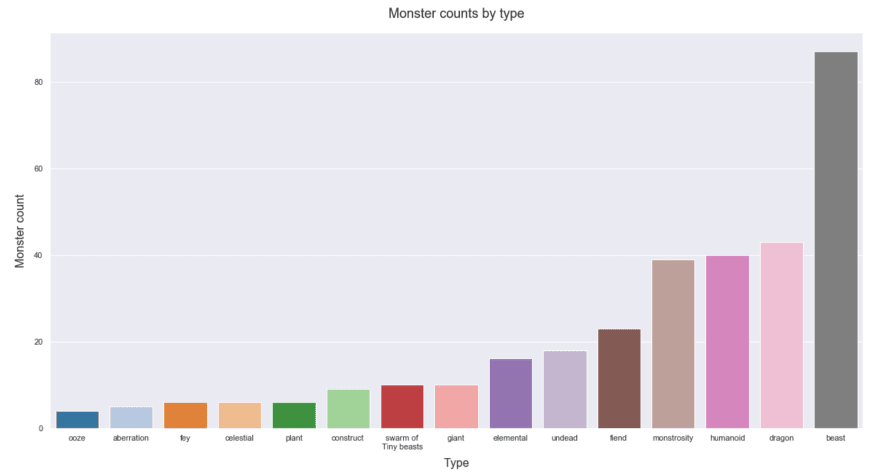

I started just by counting up the monsters for each type. “Beast” was by far the most common type of monster, followed by “dragon”. Dragon being one of the most popular types makes sense - given the name of the game - but I was disappointed to discover that that’s mostly because there are a whole bunch of different sub-types of dragon (red vs. black vs. green, and so on) and that each type appears several times at various ages. This makes dragons seem more dominant in the data than I feel is strictly fair; I get that it is important to have separate stat blocks for a creature that grows so dramatically in power, but it still seems like all the many and varied humanoids get a raw deal.

I did spot an almost immediate imbalance though, linking back to the first question I wanted to answer. There are 23 separate “fiend” type monsters (basically demons), but only six “celestials” (basically angels). This violates the time-honoured principle of “as above, so below”, and suggests that, if you are a dungeon master looking to brew up some new monsters, you’re a lot more likely to come up with an original heavenly concept than you are a hellish one.

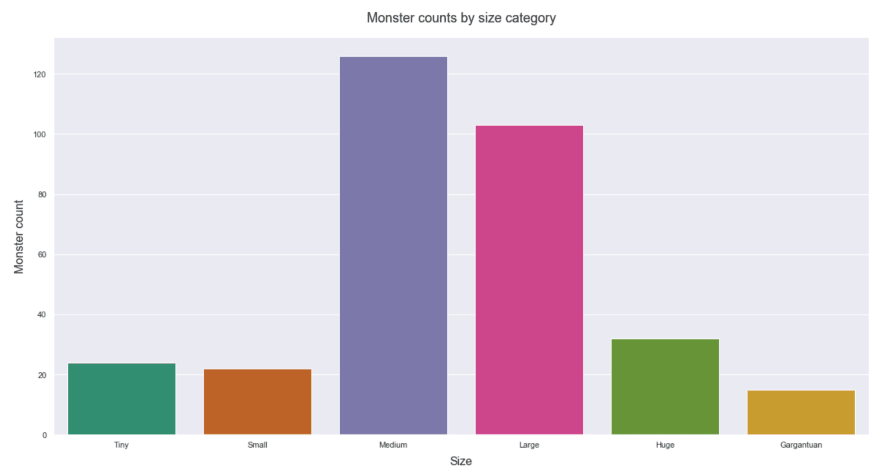

The next thing I looked at was monster size category. This seemed to show a reasonable spread: the majority of monsters were human-sized (medium) or one step larger, which makes sense both in terms of drama and providing sufficient challenge to players. A small number of extremely large monsters exist in the “gargantuan” category to provide challenge and terror.

Stat distributions

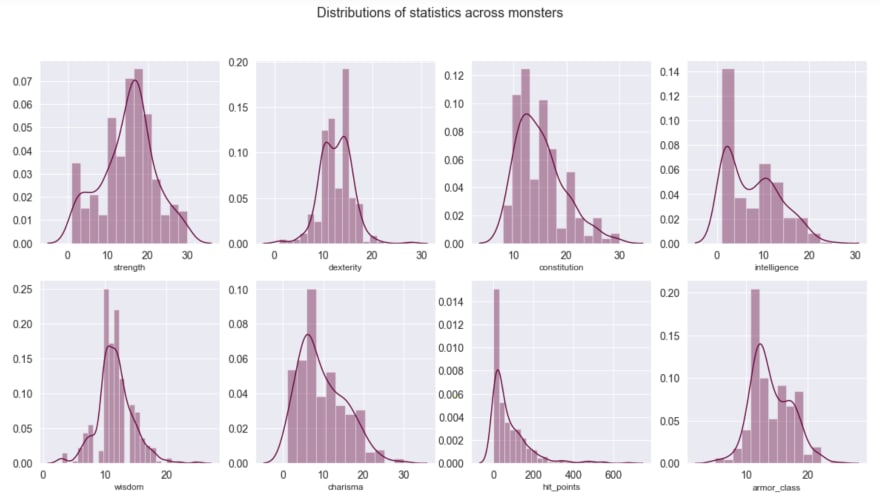

I plotted the distribution of each of the main numeric stats across the whole set of monsters. This, again, was in aid of seeing if there were any obvious under-represented monsters. There was a lot of variation present, showing that for every stat, there are monsters at both ends of the scale. A small number of monsters had truly gargantuan (see what I did there) amounts of hit points, but the vast majority of monsters fell into a smaller range.

One interesting thing did jump out to me here though - when you compare strength and intelligence, the distributions are very different. Discounting hit points because it clearly scales by other rules, you can see that the peak distribution for strength is around 16 (later than any other stat), while intelligence peaks close to zero (earlier than any other). I can see an ecological justification for it - many of the monsters are “beasts”, and cannot be expected to have great minds - but it does suggest that the majority of monsters rely on physical, rather than intellectual prowess. Wisdom, the other cerebral stat, has a similar distribution to intelligence.

“Dumb brute” seems to be a more common monster archetype than “scheming mastermind”, and I suggest that - if anyone is looking to create new, original monsters - smart ones would be more easily differentiated. Plus, they’re more fun, in my opinion; out of the three kidnappers in The Princess Bride, Vizzini is the most tense confrontation.

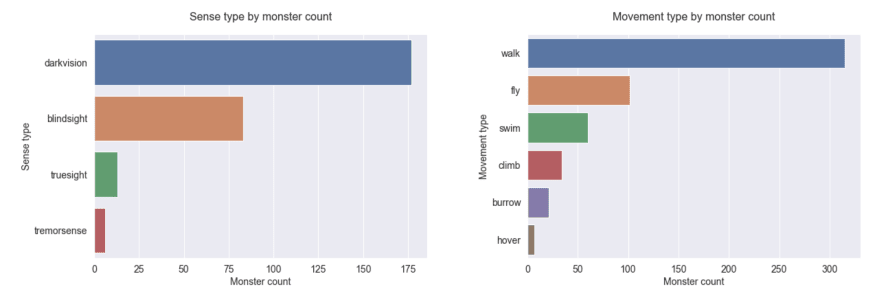

Senses and movement

Well over half of monsters can see in the dark. A respectable number have “blindsight” - they perceive the world through other senses, such as echolocation. A very small number have “truesight”, which lets them see through illusions to unvarnished reality. This seems like a reasonable progression to me, with not too many monsters having an advantage in the dark, and the more exotic abilities being more rare.

I do think that “tremorsense” deserves more related monsters though; detecting vibrations is something that a lot of real animals, such as moles, do, and some of the most iconic movie monsters ever have used it to great effect.

The movement types suggest a similar neglected niche; while almost everything can walk, and flying and swimming have reasonable monster counts, very few monsters burrow. I’d like to champion the cause of blind things gnawing through the earth, because I find them extremely terrifying and also because they seem like they’d present new & exciting challenges compared to yet another goblinoid clan.

Alignment

D&D has a moral alignment system based on two axes, one between good & evil, the other between law & chaos. Canonically, characters & monsters are given a two-word alignment description, such as “Chaotic evil” or “Lawful neutral”.

I know enough to know that there’s a whole discourse around this in terms of how consistent/meaningful alignment is, how strictly it should be considered, and whether or not it’s just a bad idea for the game/society generally. I have no plan of getting embroiled in that.

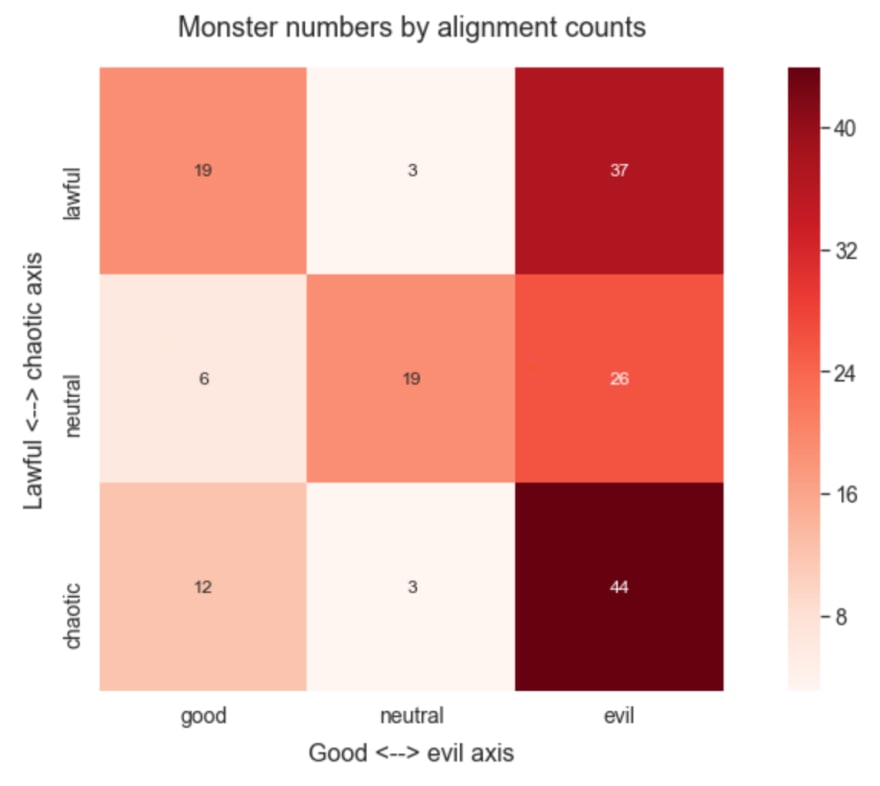

However, I was curious about the representation of each alignment amongst monsters. It turns out, somewhat disappointingly, that a lot of monsters - 128 out of 322 - are “unaligned”: they have no moral stance at all. A further few have awkward alignments, such as the Cloud Giant, which is “neutral good (50%) or neutral evil (50%)”. After removing all the unaligned and awkward though, I was able to plot the monster counts for each of the nine normal alignments.

Unsurprisingly, the most common alignments for monsters were evil ones, most commonly chaotic evil. Neutral alignments on either axis were quite unpopular, though “True Neutral” - the middle category - had quite a few occupants. Off-hand, I’m going to blithely assert that that’s probably because it’s a bit of a catch-all category. If there is a neglected niche here, it’s monsters that aren’t especially monstrous, ones that lean towards good or sit on the fence a lot.

Neglected monster niches

My first aim was to examine neglected monster niches - particular types of monster that might be less than evenly-represented in the bestiary. Based on my exploration so far, I venture to suggest that there are some monster niches that are, if not under-occupied, at least less-occupied than others. D&D will always have a disproportionate number of dragons, but if you’re looking for new monsters, there are some areas that would be more original than others.

By my reckoning, the most original and exciting monster of all would be a well-intentioned burrowing celestial mastermind. If you’re looking for further inspiration, allow me to point you towards the most celestial of all moles.

Stats and challenge rating

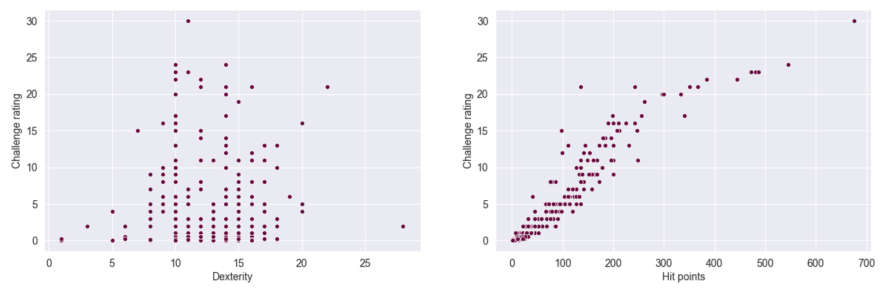

My other aim was to see how closely related monster stats are to challenge rating. To explore this, I calculated the correlations between CR and each other stat.

It’s worth mentioning at this point that this analysis rests on shaky ground, mathematically-speaking; while CR looks like a number, it’s actually a set of ordered and inconsistently-spaced categories. For that reason, plus the limited data available, I chose not to do any more complicated modelling, because it wouldn’t be very valid. Correlations suffer from the same issue, but can still be indicative as long as the above caveat is borne in mind; the correlations used here shouldn’t be taken as precise metrics, but solely as a rough way of comparing two variables.

| Stat | CR correlation |

|---|---|

| Strength | 0.72 |

| Dexterity | -0.02 |

| Constitution | 0.86 |

| Intelligence | 0.64 |

| Wisdom | 0.55 |

| Charisma | 0.69 |

| Hit points | 0.94 |

| Armour class | 0.76 |

The majority of the stats showed a clear positive correlation; this is to be expected, as the point of those stats is to quantify a creatures attributes, and a creature that is stronger/faster/smarter than another will present a more significant challenge.

Hit points, followed by constitution (which is linked to hit points and affects their growth) were the most highly correlated. This suggests that one way of increasing a monster’s CR is just to bump its health up a bit so it takes longer to kill and has more time to fight back.

The more physical stats - strength and constitution - are more correlated with CR than the cerebral ones, which, again, makes sense; I’m more terrified of intelligent enemies over the longterm, but when wrestling in a cave, I’d be more confident grappling a wizard than a cave troll.

The most interesting correlation though, was with dexterity. Unlike the other stats, which plotted against CR in broadly similar neat lines, dexterity was all over the place. There were several high-CR monsters that have relatively poor scores for dexterity, and a couple of otherwise pitiful creatures (by CR) with high dexterity; the most anomalous is the will-o’-the-wisp, with a CR of 2 but a dexterity score of 28, significantly higher than any other monster.

The D&D wiki defines dexterity as measuring “agility, reflexes, and balance”, but it seems to be used as a proxy for size in some cases, with dexterity being assumed to belong more with dainty creatures than hefty ones.To some extent, this makes sense, but it does feel slightly out of the spirit of the stat. The highest dexterity score amongst gargantuan creatures is 14, but the majority of the behemoths can fly, demonstrating that they aren’t simply lumbering beasts. The kraken has many weaving tentacles (the description in the wiki uses verbs such as “twining” when describing it) which again matches my layman’s understanding of dexterity, but is not reflected in the stat.

I’m aware that I sound rather defensive of the monsters here (I have always had a soft spot for krakens; I am unsure why), and that this is probably one of those things that would make more intuitive sense if I was more familiar with the game in practice. I think possibly the stat is thinking of whole body dexterity (how easily can you fling yourself out of the path of an arrow), whereas I’m picturing the kraken’s fine control of a single tentacle: the difference is one of nimbleness vs. precision.

I do still think it’s interesting that dexterity does not match the pattern of the other stats, suggesting that this stat is - either perceived to be or actually - less important than the others. This is definitely something that I lack the necessary domain knowledge to untangle further; if any reader can shed more light on this, I’d be very interested.

I was, overall, a little disappointed by how high the correlations were between stats and CR. I expected it to be noticeable, but not quite to the extent that it was (particularly with hit points). Perhaps naively, I wanted to find that actually the scores were less important than the fine details of the monster.

Still, there is definitely sufficient variation amongst monsters and stats to show that all those abilities and attributes do matter somewhere, albeit not to the extent that I wished. It must always be borne in mind, however, that CR itself is a crude and highly-subjective metric, heavily dependent on how the monster is played, rather than how it is written.

Final thoughts

I don’t have anything earth-shattering to wrap up with here; no big conclusions or stunning reversals. I got to explore an unfamiliar API and mine data that is a lot more interesting than most datasets floating around on the web.

I’d like to experiment further with the API in the future, perhaps trying to generate new spells based on the descriptions of existing ones; unfortunately (because generating monsters would be the most fun of all), the descriptions of monsters are not available through the API.

I enjoyed playing around with this data, and I found sufficient things to amuse me in it; it is my fervent hope that anyone who read this far down the post found it at least a fraction as interesting to read as it was to write.

If anyone has suggestions for further avenues of analysis, I’d love to hear them. If anyone would like to clarify or explain anything that confused me (like the dexterity correlation), I’d be extremely interested in that as well. Please do get in touch.