Book Recommendations with TF-IDF

09 May 2020I’ve been working with TF-IDF a lot as a metric recently, teaching first myself, then other people, how to calculate it. However, actually using it for anything interesting was a further step.

In order to combine both my interest in literature with my desire to put TF-IDF to use, I created a book recommendation system in Python, using TF-IDF to calculate the most similar books based on their descriptions.

Aims

My aims for this project were to answer two initial questions:

-

What are the most popular words in book descriptions?

-

Does TF-IDF effectively distinguish between different books?

In addition, and primarily, I wanted to build a recommendation system that could make reasonable predictions based on short descriptions alone.

Motivation

I was motivated to complete this project by three factors, listed in ascending order of importance:

- Completing an independent project forms part of the Udacity Data Scientist Nanodegree, so I had to.

- I wanted to play around with TF-IDF to cement my understanding of it.

- I was curious as to how useful book descriptions actually are in differentiating books from one another and finding similar titles.

TF-IDF

TF-IDF stands for “term frequency-inverse document frequency”. In short, it’s a way of measuring, for a given word in a given document, how important that word is to that document. Unlike many other measures of word importance, TF-IDF controls for the simple, functional words (such as “the”, or “and”) that are extremely frequent in all texts, but do not carry much meaning themselves.

If you just rely on the simplest metric for word importance — raw frequency of a word — then the word “a” is one of the most important in almost every document. However, using TF-IDF, only words that are common in that document, but rare generally, are seen as important.

Using TF-IDF to find similar documents

If you have a set of documents, and a set of words, you can calculate the TF-IDF score for each word for each document. The list of scores for a given document is a TF-IDF “vector”, which can be understood (colloquially, roughly, but usefully) as a location in an imaginary hyper-dimensional space.

By finding documents with TF-IDF vectors that are similar — locations in imaginary space that are close together — you can find documents that should, ideally, have similar content and ideas.

Data source

The data for this project was sourced from Kaggle: a dataset of popular books on Goodreads. The dataset has around 50,000 rows, and for each book records (amongst other information) the title, author, and description.

Code

All the code written as part of this project can be found on GitHub.

Data cleaning

The data needed a lot of cleaning before it was in a fit state for analysis. The dataset contained many effectively duplicate rows, where books differed only in edition number, misprinted title, or in the language of the description. After cleaning the data extensively, I was left with just over 37,000 separate books, with 17,000 unique authors. Only books with unique, English descriptions were preserved.

There were further problems as well — book descriptions on Goodreads are often user-entered and contain errors or simply aren’t that descriptive. With this dataset, there wasn’t really a way around that other than manually cleaning and checking all 37,000 descriptions, which I declined to do; these issues must be borne in mind when thinking about the generalisability of any results.

Data analysis

The first step was to process the descriptions into a simple and consistent form. To this end, I converted all descriptions to lowercase, before lemmatising each word in each description, and filtering out common “stop words” — words that appear frequently in any document, such as “and”, but that do not have much relevance to the actual topic of the document.

The above steps meant that each description was reduced to just its most important words, the words that were most descriptive of the book itself.

Once all the descriptions were reduced into just keywords, I was able to not only identify the most popular words over all descriptions (required for my first aim), but also to calculate the TF-IDF vectors for each description, which was necessary to meet my other aims.

Once I had calculated TF-IDF vectors for each description, I was then able to use cosine similarity (a mathematical method to calculate how close two different vectors are) to identify the most similar other vectors to a given TF-IDF vector, and thus identify the most similar books to a given book.

Results

What are the most popular words in book descriptions?

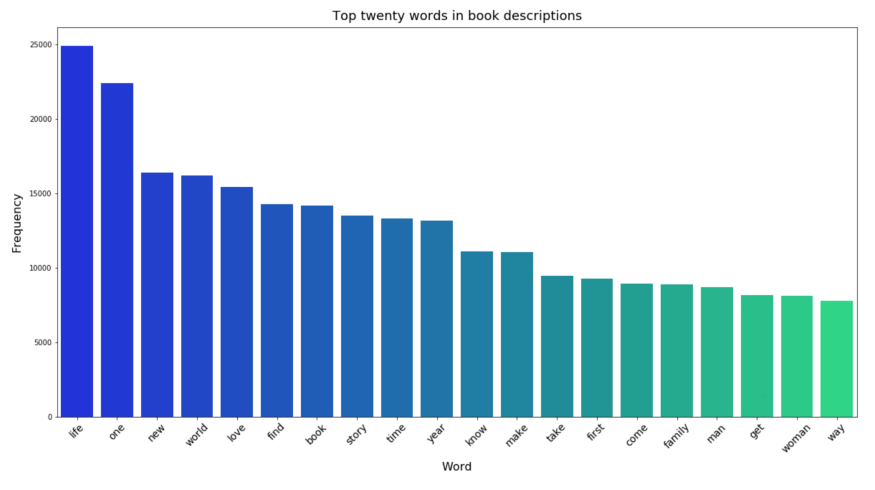

The visualisation below shows the top-twenty most frequent terms found in book descriptions (once stop words, etc., had been removed). “Book” is number 7, for example, which makes sense.

Most of the words are relatively unexciting, which is to be expected — the most common terms across all books will be the most generic. However, it is interesting to see that “life” was the most popular of all, and that “man” and “woman” featured roughly equally.

Does TF-IDF effectively distinguish between different books?

In a word, yes. After cleaning and processing, only 24 books shared TF-IDF vectors with each other, and these were books that had a huge amount in common: Learn Spanish and Learn Dutch, for example, were two books from the same publisher in the same range, and there was little to differentiate their descriptions — the TF-IDF vector only records a limited number of words, and neither “Spanish” nor “Dutch” was significant enough across the whole dataset to warrant inclusion.

The vast majority of books were distinguishable by their vectors, suggesting that this is both a good metric, and that those 24 duplicate books were only duplicates due to poor descriptions that gave little distinguishing information.

Building a recommendation system

Using TF-IDF and cosine similarity, I was able to make a simple a recommendation system that simply returned the five most-similar books to a given description. When I tested this on books that existed inside the dataset, the first book returned was always the book itself, which — while not an interesting prediction or valid measurement of success — serves as a useful sanity check on the vector similarity calculation.

Generally, book recommendations were appropriate, with books of mainly the same genre being suggested for a fantasy book’s description, for example. Occasionally, there were some odd-but-understandable suggestions, such as the suggestion of Emily of Deep Valley (a book about a young woman who is led through duty to her family to love) for The Meg (a book about an aging man with a collapsing marriage who hunts a prehistoric shark). While these books have little similarity in terms of theme, tone, or genre, they do both feature the word “deep” extensively in their respective descriptions.

TF-IDF is an effective metric, but a relatively crude one, as the same words can appear in different contexts (“deep” in rural Minnesota and the Marianas Trench). Other than such confusions though, the recommendation system was reasonably effective, and — while not always suggesting the best possible match — at least suggested books that were not totally different.

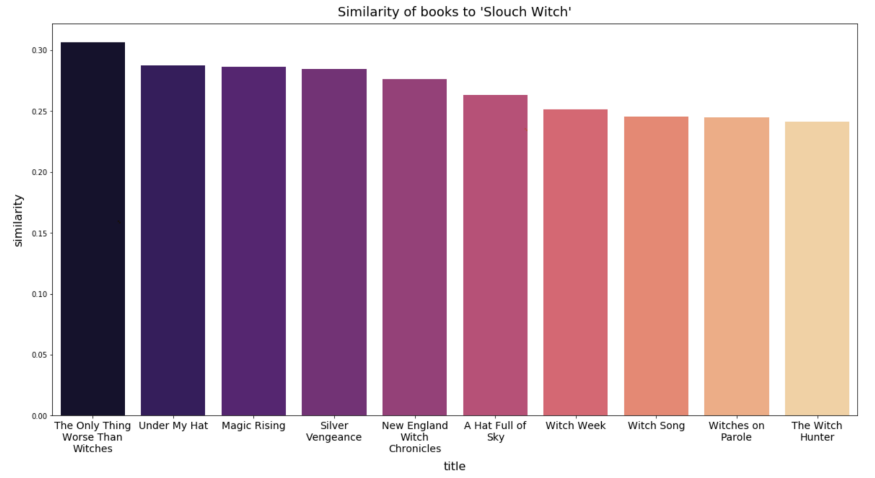

The most similar books to Helen Harper’s ‘Slouch Witch’ are all fantasy books about witches.

Conclusions & next steps

It’s something of a cliché, but I’d like to run this same analysis over a better dataset — one with fewer duplicates and fewer errors in the descriptions. The ideal would be working with the official blurbs of the books themselves, rather than a user-entered description. I think that would lead to more meaningful recommendations. I’d also like to explore named-entity removal to cut down on false matches on protagonist names or locations.

It’s worth mentioning that technically, the recommendation system works with arbitrary text data, not simply book descriptions. I’ve found it relatively entertaining to find the most similar books to the Wikipedia pages of particular people, for example (diplomats tend to end up with John le Carré novels).

Overall, I’m happy with this project — it’s not the best recommendation system ever, but it’s a workable one, and I’ve learnt a lot about TF-IDF by working through it. I have new ideas for new things to do next, building on this and extending it.